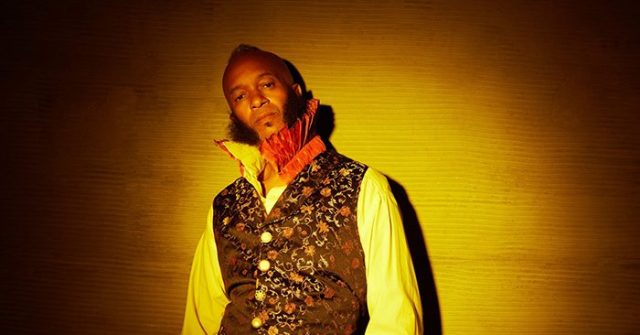

His name used to be Xavier Amin Dphrepaulezz, but Fantastic Negrito didn’t mention that. He also didn’t mention the accident that left him in a coma for three weeks and robbed him full mobility of his hand. He didn’t mention winning three Grammys in as many years for Best Contemporary Blues Album. He didn’t even mention couch-surfing in Los Angeles as he worked to build his name in music.

Even so, Fantastic Negrito was able to drop a bombshell that contradicts what’s reported on dozens of websites including NPR and Wired and CBS News.

This first-generation Somali-American isn’t.

Mshale’s attention was grabbed when Fantastic Negrito was booked to perform at The Dakota Oct. 25. Fantastic Negrito, raised in a strict Muslim household by a Somali-immigrant father, seemed an ideal story of a first-generation Somali-American.

That was before he left us speechless with this news about his father’s immigration status, a story that’s been passed along for dozens and dozens of years.

“That’s one of the things that I discovered was a complete lie,” Fantastic Negrito said during a Zoom interview with Mshale.

“I [also] discovered that my dad created this name [Dphrepaulezz], which is unpronounceable to most people in order to give himself an upper hand during the 1920s and 30s,” Fantastic Negrito said.

In other words, Dphrepaulezz, Sr. was more than a self-made man. He was also self-invented.

“My dad was born in 1905. He was a pretty fascinating person. He faked an identity in the early 1900s in order to basically trick white people into thinking he was someone else. He had a name that was extremely different. He had a previous life and previous marriage and children of whom he’d never spoke.…[but] I think he was just able to get a lot of things done [through his deception].”

Why would he do this?

Fantastic Negrito postulated on his now deceased father’s reasons for his deception. “He tried to give us some identity that wasn’t just based on slave-trade,” he said.

While Dphrepaulezz, Sr.’s immigrant status was fabricated, his connections and investment in the Somali diaspora were genuine and deep. In the 1920s, Somali immigrants first arrived in the United States as sailors from British Somaliland.

“My dad,” said Fantastic Negrito, “had very strong ties with that community, with Abdullahi Issa, [Prime Minister of Italian Somalia] and Ibrahim Guled. It’s very heavily documented that he…that my father did assist that group of Somali people that were seeking independence.”

“You gotta remember, my dad was born in 1905 [during] that Pan-African movement,” Fantastic Negrito said. “I think he got the Somali thing…that very intense close ties and helping the Somalis achieve their goal of independence from their colonial masters was important to him.”

“He played this whole act at being [of] Somali heritage until he died,” Fantastic Negrito said.

Discovering the cock and bull story didn’t stop Fantastic Negrito from reaching deeper into his ancestry and finding an authentic immigrant story to inform his most recent film and album, White Jesus, Black Problems.

“I discovered during the pandemic as I told you about the story with my dad, on my [maternal] side, there was a union between an enslaved African and a white Scottish indentured servant so I made a film about that,” Fantastic Negrito said.

A union, by the way that was illegal as well as socially verboten in 1750s America.

His show at The Dakota will be about White Jesus Black Problems. “I’m premiering that film in the Minneapolis market and then afterward we just talk and play acoustic. That’s really what’s gonna happen, which is incredible to tell the story of my seventh-generation grandparents who really got some s-t done,” he said.

“We live in an era now where people can’t get anything done. And it’s totally polarized. Either you’re all the way to the left or you’re all the way to the right and we seem paralyzed and we can’t agree on anything but what I found fascinating and inspiring about my seventh generation grandparents is they got something done in an impossible time and in an impossible place. So so much love and respect for them and they inspired my 40-minute film.”

By: Susan Budig (Mshale)